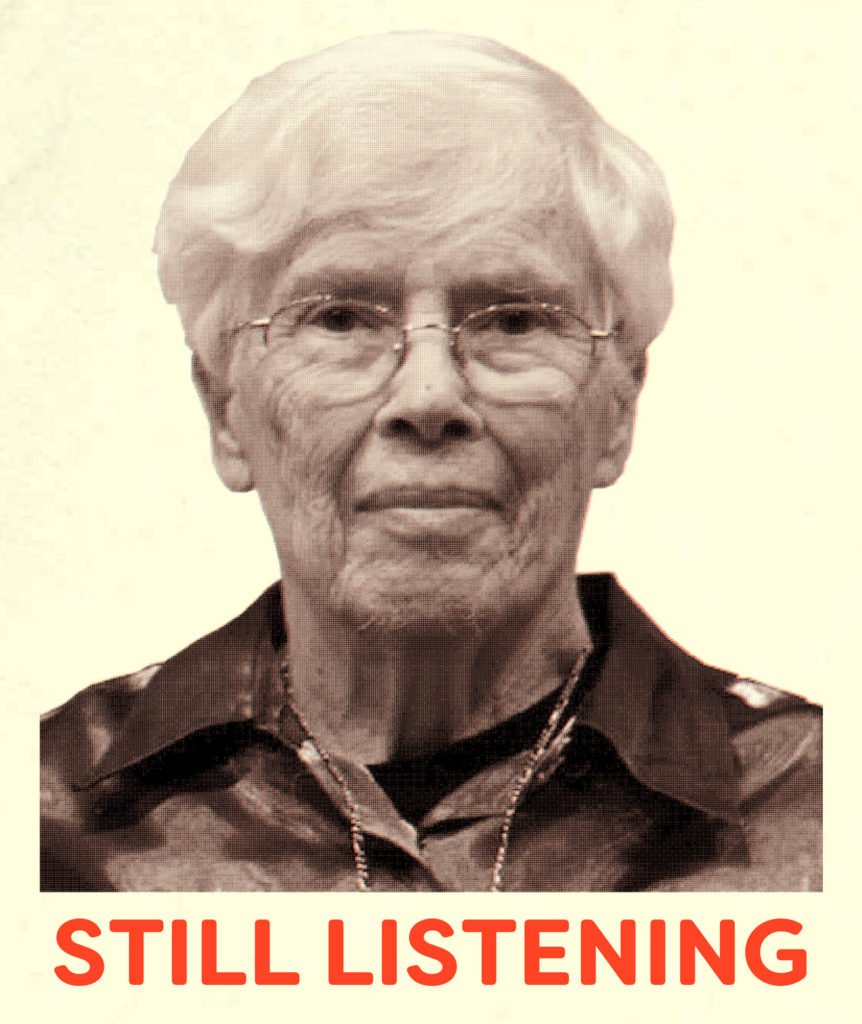

Deep Listening is listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing. Such intense listening includes the sounds of daily life, of nature, or one’s own thoughts as well as musical sounds. Deep Listening represents a heightened state of awareness and connects to all that there is. As a composer I make my music through Deep Listening.

Pauline Oliveros, composer & musician

Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016) was a pioneering electronic musician and composer. She founded Deep Listening and developed it over 40 years with many other people in a continually growing international community. She founded the The Center for Deep Listening, in Troy, NY, which offers certification courses in Deep Listening. I spent a year getting certified in Deep Listening, and continue to facilitate sessions, primarily at conservation sites.

Pauline often told the story about when she first started teaching. It was at a conservatory. Her students were learning to be classical musicians. She noticed that they would perform, but would not listen to each other. She developed techniques to get them to pay closer attention to the sounds they were making, how the sounds behaved, and how the sounds impacted their fellow students and the spaces they performed in. These initial efforts eventually were explored and developed into what is now called Deep Listening.

The three main components of Deep Listening are: listening, moving and dreaming. A student of Deep Listening is trained to learn to listen and develop awareness in these three areas. From the beginning, one is taught to understand the difference between hearing (passively receiving sound) and listening (actively giving one’s attention to what is sounding—that is, what is making sound). This publication focuses on the aspects of Deep Listening that include the combination of listening and moving.

Sound is either being sent or received. You often experience both simultaneously. You are constantly experiencing situations where your surroundings are sending many sounds while you receive them and send your own back. A common situation is when I am talking to a friend, I am sending sound, and we are both receiving it in order to make meaning or understand the purpose of the sound.

There is no sound without silence; the inverse is also true: there is no silence without sound. They are two intermingled states that rely on each other for us to make sense of what is sounding or being received around us. One can listen to sound just as easily as one can listen to silence. Sounds and silences have particular shapes, durations, tones, and other qualities that one can discern when giving close attention. An easy way to demonstrate the presence of silence is to have someone stand in front of you and to clap your hands around her showing all the silences that were waiting to receive the clapping. Another example that helps you understand how much silence you are constantly hearing, if not listening to, is to look at clouds floating way overhead and to imaging fireworks exploding in their midst. You would be able to immediately locate the sound. For this sound to have an understandable location, duration, and strong presence, you must have already been listening to giant spaces of silence. If they were not silent, then you would not have been able to have heard or located the firework.